“A parking space is nothing less than the link between driving and life itself, the nine-by-eighteen-foot portal through which lies whatever you got in the car to do in the first place. Whoever said life was about the journey and not the destination never had to look for a place to park.” — Henry Gabar

Having lived car-free since 2012, I have blissfully avoided the trials of parking meters, tickets, and the anxiety of finding a spot in a crowded city. My journey without a car has liberated me from the dreaded dented doors and shattered windows that come with parking in urban environments.

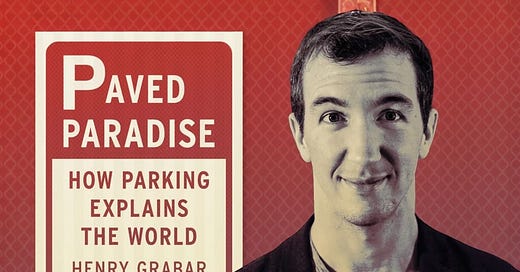

For many, parking is more than just finding a place for a vehicle; it is a daily battle that shapes their lives. It’s here where Henry Gabar, author of the book, “Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World” dives into how parking, an unglamorous aspect of urban life, plays an outsized role in city planning, real estate, and our day-to-day routines.

My long time friend Devorah who is car free in the Boston area paints a vivid picture of her local four-wheel friends. In Brookline, a town in the metro area, traffic snarls and limited street parking force residents to pay top dollar for driveways rented from homeowners.

During the Fall amid move-in days for students at nearby Harvard, Boston College, and MIT, already scarce parking becomes almost nonexistent. Moreover, the logistical nightmare of navigating the city—often requiring multiple modes of transportation—makes car ownership feel more like a convenience than a liability.

Henry Gabar’s work captures this reality through a sociological lens, unearthing the ways parking availability drives urban expansion and influences our choices. In cities like Boston, Chicago, and Los Angeles, the story of parking is one of constant evolution.

Gabar eloquently describes a parking space as the “nine-by-eighteen-foot portal” linking driving to everyday life, underscoring how parking impacts everything from the size and cost of buildings to the viability of public transit and the character of neighborhoods.

Parking determines the size, shape, and cost of new buildings, the fate of old ones, the patterns of traffic, the viability of mass transit, the life of public space, the character of neighborhoods, the state of the city budget, our whole spread-out life in which it is virtually impossible to live without four-wheels.

Photo Credit (Phoenix, AZ) — Diamond Michael Scott

The irony of parking is that it often feels like a public right, yet it's increasingly becoming a private commodity. In Sacramento, California’s capital city, for instance, the changing parking landscape mirrors the city’s growth. New residential and commercial developments are pushing the limits of available spaces, prompting a range of strategies to meet demand—from adding new parking structures to encouraging alternative transportation methods like biking and public transit.

Gabar’s observations about parking as an often overlooked but crucial urban component align with the experiences of residents like Vinny Catalano in East Sacramento. Vinny’s stories of near-misses with parking tickets and the challenges of navigating public garages reflect a broader truth: parking is not just about finding a space; it’s about navigating a labyrinthine system of regulations, fees, and time limits that can turn an otherwise simple task into a daily stressor.

As Gabar notes in his book:

“Driving into a new city, I often find street-parking instructions so unintelligible I might as well be trying to read a restaurant menu from twenty feet away, through a window, while steering the car. No aspect of American law is as scorned as parking regulations; no civil servant is as despised as the parking agent, which must be the only job whose workers say they cover up their uniforms to eat lunch, out of concern that someone will spit in their food.”

In cities like Davis, just west of Sacramento, the parking dynamic is driven largely by its identity as a college town. With over 35,000 students at UC Davis, the demand for parking is unrelenting. The city’s commitment to sustainability means that bicycles are often the preferred mode of transport, a solution that alleviates some parking pressures but does not entirely erase them.

Meanwhile, in downtown Sacramento, parking garages that once bustled during business hours now see fluctuating occupancy, tied more closely to the rhythms of events at venues like the Golden 1 Center.

Gabar’s exploration of parking touches on the environmental impacts as well, highlighting how parking requirements have historically driven urban sprawl, contributing to heat islands, flooding, and increased stormwater runoff.

As cities grapple with the rise of autonomous vehicles and changing work patterns post-pandemic, the future of parking could look radically different. Self-driving cars, for example, promise a world where vehicles drop off passengers and park themselves, possibly far from urban cores, reducing the need for vast parking lots that currently dominate our landscapes.

Ultimately, Gabar’s book and my lived experience underscore a fundamental truth: parking is not just about convenience; it’s about how we organize our cities, shape our environments, and, ultimately, how we choose to live our lives.

For those of us who have stepped away from car ownership, the freedom from parking woes is a sweet reminder of the hidden costs that come with driving—a perspective that perhaps more of us will embrace as cities continue to evolve.

I am a former urban journalist who has written hundreds of feature articles for publications like Comstock’s Magazine, Governing Magazine, New Geography and many others. You can support me in building this city-centric digital community by becoming a free subscriber or member supporter.

Every little bit is appreciated.

Diamond-Michael Scott